If you haven’t heard those famous last words from the biggest ego-lifter you know, you’ve definitely heard one of my other personal favorites: “it works for me, bro”. In this article, I’ll be examining why taking a more measured approach in your training can yield HUGE long term benefits that will get you stronger than you could theoretically get with training recklessly.

I’m Biased.

Before we dive in, I’d like to preface this article with the fact that I’ve been subject to this stream of thinking in my younger days as a lifter, so I do have some bias with writing this article. I’ve had a number of injuries in those early years that I feel were easily preventable with proper coaching and technique correction.

While nothing is a guarantee, I take a look at the injury occurrence between lifters with what many would consider “bad” form (ex. the roundest back deadlift you can imagine) and those with “good” form (ex. neutral spine) and more often than not, I see those lifters with bad form get very predictable injuries. While there is some personal bias and empirical thinking in this article, my goal is to back it up with objective research so you can have some facts to work with and extrapolate on data instead of my own personal experiences.

As everyone’s muscular strength and body proportions will differ (amongst other factors), there is no “one true form” for the powerlifts. That being said, there are some generally accepted guidelines for “good form” with the squats, bench presses, and deadlifts.

|

|

General Guidelines |

|

Squat |

· Knees track over toes, · No significant knee valgus · Using intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) to ensure spine stays stable in a slightly extended, neutral, or slightly flattened position · No excessive motion through the vertebrae · Feet flat on the ground with weight distributed over mid-foot · Bar path relatively straight up and down |

|

Bench Press |

· Scapulae retracted and depressed throughout the lift · Elbows aligned with wrists to promote a shoulder position that is not too internally or externally rotated · Butt stays on bench · Some thoracic extension to promote upper back tension |

|

Deadlift |

· Using IAP to ensure spine stays relatively neutral through the lift · No excessive flexion in starting position · No dynamic flexion under loading (rounding over as you start the pull) · Keeping lats tight through the lift to keep the bar close to the body and protect spine. · Relatively straight up and down bar path |

The above suggestions are generally accepted to be a good starting point for the majority of lifters which optimize force production, put the lifter into a strong position where force is relatively evenly distributed across the body so as to not overly concentrate on one joint/muscle, and mitigate injury risks. Theoretically, this style of lifting could improve your long term results even if you do have to take a step back in weight initially. While injury isn’t a guarantee, nobody cares how fast you got to a 225lb bench press as a 180lb male if you never get past that because you keep injuring yourself.

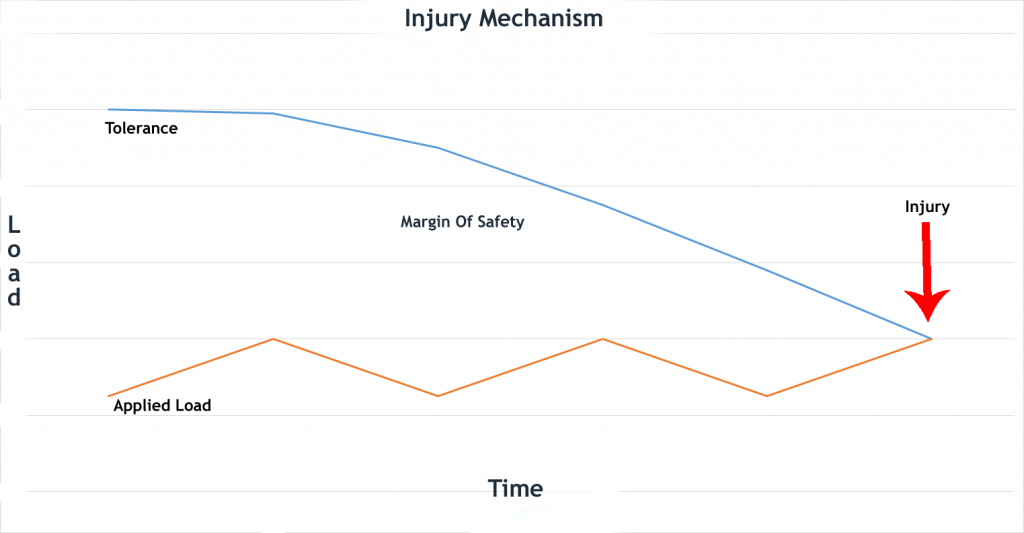

Going back to our example of the round back deadlifter, it’s been clearly studied that extreme flexion (like you see in an extremely rounded back deadlift) coupled with loading puts significant stress on the discs and vertebrae in the back. Over time, this disproportionate stress on tissues which recover much more slowly than the muscular system leads to a decline in loading tolerance (blue line) until eventually, you might hit that point where you get injured “because of that one rep”. While acute injuries do happen, a LOT more of the injuries I see as a powerlifting coach and rehab specialist are chronic in nature and require fixing patterns that led up to the injury (Adams MA, Hutton, WC, Gradual disc prolapse. Spine 10: 524, 1985).

So, how should you train, given that there is an inherent risk to just about everything you’re going to do at or outside of the gym? Injuries aren’t a guarantee, but distributing the loading more equitably across tissues with higher recovery capacity or load tolerance seems to be the recurring theme in a lot of injury mitigation methods.

A Tale of Two Lifters

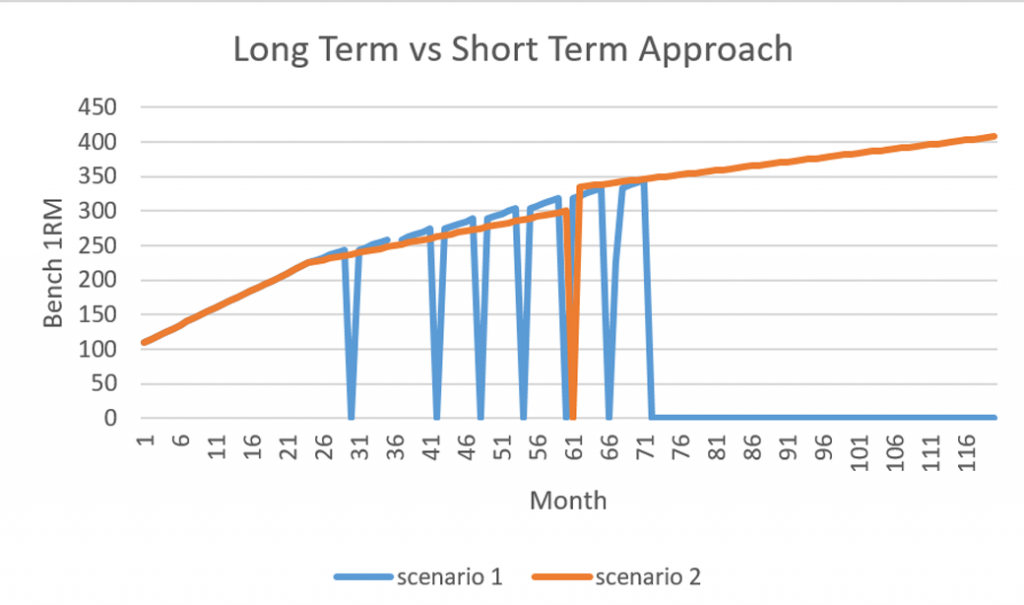

Let’s take a look at 2 scenarios to illustrate how “not being hardcore” can actually make you stronger. Keep in mind, none of the values below are absolute, they are just for illustrative purposes.

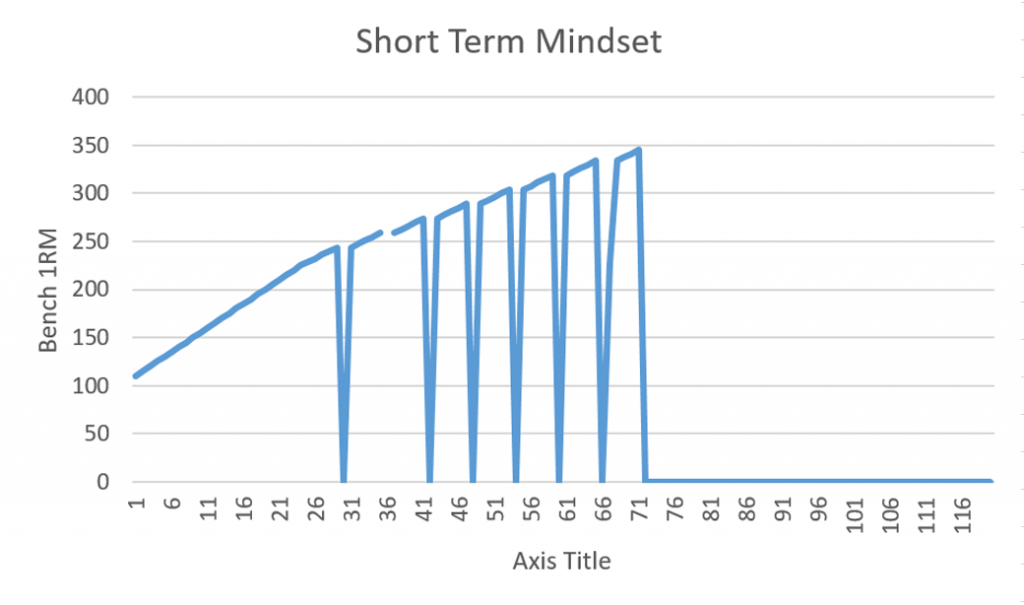

Scenario 1: You train for 2 years and go nuts with training, build up to 225lb bench, and aim to add 45 lbs per year to the bench so you can bench 360lbs by the time you’ve been lifting for 5 years. You get injured often because of your shoulder blades being very unstable and putting a lot of stress on the muscles of the rotator cuff and never taking the time to address it. You keep the same shit form after each injury, learn nothing, and get injured every 6 months needing to take 8 weeks off to heal and rebuild. Every year of training you do leads to only 8 months of productive training. After 5 years, your best bench is around 318 lbs and your shoulders hurt all the time. The severity of the injuries gets worse and it takes you longer and longer to recover from each subsequent injury until you decide that powerlifting isn’t for you because bench press always bothers your shoulders. After 6 years, you stop training. You deem the bench press a dangerous exercise and never really do anything significant with your bench training. You can only get so strong this way.

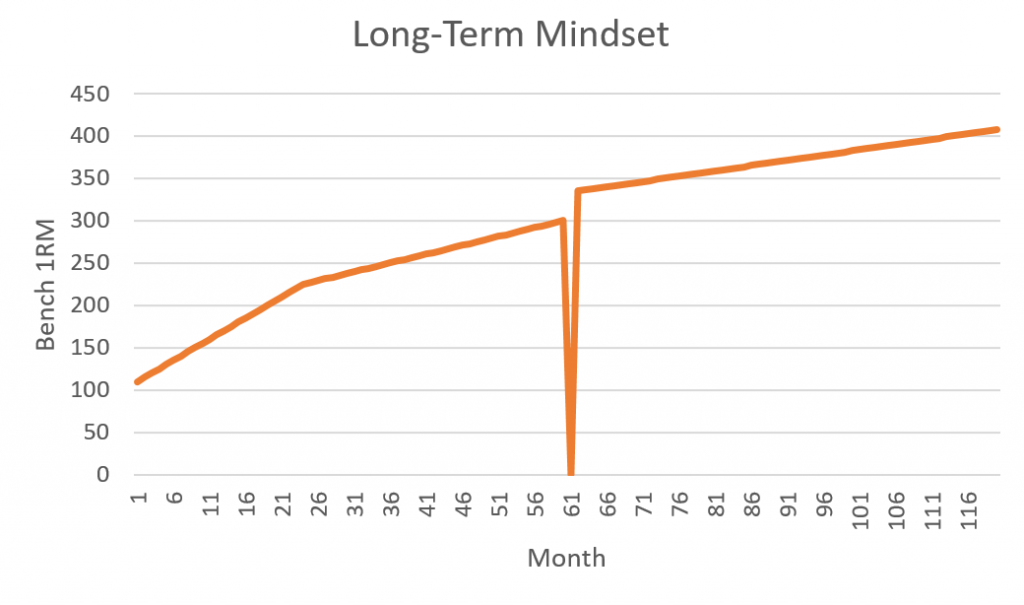

Scenario 2: you take a slightly more measured approach and stick with loads that you can manage properly, keep your shoulder blades retracted and depressed for 95% of your training. You focus on getting stronger with appropriate form in the name of being able to train 1, 2, 5, or 10 years from now. After the initial beginner gains, you add about 25 lbs a year (2.1lbs a month) to your 225lb bench press. You have a pec strain due to an off day at the gym on year 3 and take 8 weeks to rebuild to where you were at before the injury and as such, only add 20lbs to your bench that year. After 5 years, you have benched 320lbs. On years 6-10 you sustain one more injury on year 6 which puts you out for another 8 weeks, but otherwise are able to add 15lbs per year to your bench press.

By the end of 10 years, you have now benched 407.5lbs AND you can keep going if you want.

Given then unless you’re an absolute genetic freak, strength takes a long time to build. A REALLY long time, frankly. As such, looking for a 2 year solution on how to become the next world champion is foolish. If you want to be really good (or even the best) at something, you’d better be ready to lock in for the long haul.

Wrapping up, it would seem that a lot of the lifters who justify using “bad” form on a particular exercise to squeeze 20 extra lbs out of it either never learned how to perform it safely and are unaware of the risks of certain techniques, or have a very short term, ego-driven mindset where they think if they push hard enough, they will be the best.

As much as I would love to say hard training, proper diet, solid sleep, and social sacrifices are all it takes to become a world champion, that’s something that’s just not in the cards for everyone. Instead, focus on building yourself up to be the strongest lifter than you can be, within your own limitations. Understand that if everybody could be the very best, nobody would be. The odds of you being the next Ray Williams because you added 5 lbs to your squat by lifting your heels off the ground instead of addressing your ankle mobility limitations are so slim, I’d go so far as to say it’s not worth it. Building longevity into your training program is one of the most crucial elements that gets overlooked or ignored quite often.

PS – Here’s 3 ways I can help you get stronger:

3. Apply to join my “Momentum Program” and become a case study. We’ll work with you 1-on-1 (in-person or online, depending on location) to consistently increase your PRs.

It takes less than 60 seconds to apply HERE in order to find out more information and see if you’d be a good fit.