You breathe all day, every day. When you get tight for a big lift, you take a big breath in order to brace. That’s it, right? You would think so, but often I see lifters who aren’t creating a brace effectively, or even at all since breathing and bracing are different things, and like most items in powerlifting, there’s a right way and a wrong way to do it. Today’s content is aimed at helping you to understand the basic mechanics of breathing and bracing, identify any errors you are might be making, and how to correct them.

1) The Pop Can Effect

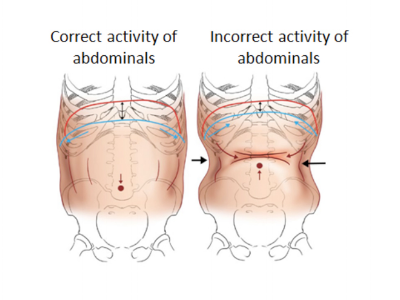

when you breathe and brace properly, it creates what we call the “Pop Can Effect”. In effect, as you breathe in, your diaphragm descends, which in turn presses outwards on your anterior and posterior abdominal wall. In proper alignment, this happens without a hitch.

However, inhalation can also occur without enough diaphragm descension. The lifter in this case will generally flare and elevate the ribcage as the lungs “hyper inflate”. While this does take care of getting enough oxygen into the blood, it does not create the intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) that we seek when trying to brace well and lift heavy weights.

2) What Does a Mistake Look Like?

With the above in mind, we see mistakes in powerlifters occur in one of two main ways. We will use the squat as an example here, but it applies to any lift where IAP is required.

Lifter 1: The lifter is over extended and “spills out” of the front. These are your lifters who can get a nice deep belly breath without chest rise, but their backs are often over extended and as the lifter inhales, they lack expansion in the obliques and posterior abdominal wall. There is diaphragm descension here, but the position of the ribs and pelvis orient the diaphragm to point forwards more than down.

Lifter 2: The lifter does not get noticeable expansion in the midriff, and their air goes into the upper back or chest. Here, the lifter is not engaging the diaphragm properly and as such has to breathe with their lungs too much, resulting in a lack of IAP. These lifters are especially prone to rounding over in the squat.

A quick note on both lifters: it’s quite common to see athletes who have the ability to brace well and not show many of the errors outlined above UNTIL they have to breathe. The ability to maintain IAP while breathing is often overlooked, but is critical to building a high performance brace.

3) Fix Yo’ Self

Once we’ve identified which category you fall into, it’s time to get to work. Refer to the video for details, but below I’ll outline the framework for each theoretical lifter.

Lifter 1:

- 9090 breathing with reach

- Dead bug breathing with reach

- Bodyweight squat with a focus on maintaining IAP

- 2-db goblet squats

- Comp squats

Our general plan of attack with Lifter 1 is re-establishing good breathing mechanics by allowing for more posterior expansion of the abdominal cavity in the 9090 position. After that, we introduce the same position, but with load to challenge their ability to integrate breathing with bracing and maintaining IAP throughout the duration of the set.

After we’ve established proper breathing and bracing mechanics, we start to work on the affected movement (squats in this case), and load technique progressively by starting with a 2-DB goblet squat which allows the lifter to more easily find a brace, then eventually moving into a competition squat technique.

Lifter 2:

- All 4’s belly lift

- 3-point belly lift vs wall

- Bodyweight squat

- Front Squat

- Competition Squats

With our second lifter, our plan of attack is slightly different. We are using gravity to our advantage to allow for more diaphragm descension and to stop them from breathing into their chest with the all 4’s belly lift, then introducing load to challenge their stabilizing patterns with the 3-point belly lifts.

As we get off the floor, things start to look more similar to Lifter 1 by introducing a bodyweight squat, followed by front squats which allow for better diaphragm positioning and discourage most of the mistakes Lifter 2 is prone to making. Our cherry on top is getting back to comp squatting.

Our time-frame for these plans to take the lifter from breathing on the floor up to a competition movement can be as short as 15 minutes, up to several weeks, depending on how patterned and body-aware the athlete in question is. Make sure you can own the technique on each progression in the sequence before moving on to the next one. If you’re not sure, give it more time at the basic exercise before leveling up as you’ll only make it harder to do things right by progressing too quickly. Pick weights you can handle as a little step backwards now can lead to huge steps forward in the near future.

PS – Here’s 3 ways I can help you get stronger:

3. Apply to join my “Momentum Program” and become a case study. We’ll work with you 1-on-1 (in-person or online, depending on location) to consistently increase your PRs.

It takes less than 60 seconds to apply HERE in order to find out more information and see if you’d be a good fit.