Never in my nearly 13 years of lifting and training have I heard of somebody who WANTS to get injured (big surprise, I know). Unfortunately, due to the need to always push the envelope in powerlifting to get that next PR (like with any sport), injuries happen. While some of these injuries are more preventable than others, there are certainly ways to mitigate your risk of snapping yourself up. In this article, I’ll be going over some key ways to do so by way of: having a plan, understanding the Mobility-Stability-Strength Hierarchy, including variation in your training, and keeping a long term outlook with your programming.

Before we get started, I’d like to take a moment to point out that absolutely NONE of the ideas outlined below matter if you don’t have a proper training program and understand your needs in the first place. If you haven’t already done a needs analysis and developed your training program accordingly, either do that first or have a qualified coach do it for you. Not having that data before designing a program is guesswork at best and questionable program design leads to questionable results.

With that said, let’s get down to biznass.

- Develop Mobility First

Once you have a training program in place, you want to use the Mobility-Stability-Strength (MSS) process to determine the range of motions you can safely use. In short, in order to develop maximal strength, you need to first have appropriate mobility and stability. Without the mobility and stability, you will never fully develop the ability to create tension as you will be compensating and “leaking” power.

If you don’t have sufficient mobility to achieve a specific position in a movement, don’t train it as you will compensate. Similarly, if you are hypermobile, creating enough stiffness (see stability below) is of utmost importance as you will tend to “hang” on your connective tissue more instead of creating your own tension with the muscles required for positions. Isometrics are your friend in this case. Powerlifting mobility work tends to be comprised of lots of PAILs and RAILs as well as static holds. While there are a number of ways to develop mobility, I feel that most lifters have enough mobility to do the powerlifts to competition specifications, they just lack the skill/coordination/stability to do the lifts well enough to express that technique. This is where developing stability work comes in.

After developing sufficient mobility, it’s time to develop the stability through the specific joints or movement that you are training for. Within a powerlifting program, this can come in a few forms. I would always start out with ensuring that the lifter is breathing and bracing properly. Without this key component, it is impossible to create stability as the lifter will always be compensating around a central instability.

Once breathing and bracing mechanics have been taken care of – depending on the needs of the lifter – a more localized joint-by-joint approach such as CARs can be very useful. If a more skill based approach is needed, using variations of the powerlifts such as tempo and isometric (pause) work can be extremely beneficial at improving stability throughout movements. The advantage with the more specific approach is that much of this training doubles as regular powerlifting training so it is a very small additional time investment. That being said, CARs and other joint control approaches have their advantages if a specific control deficit has been identified.

For more information on how to use CARs and improve your overall mobility, I HIGHLY recommend looking into my friend Leanne Kedrosky’s content. She regularly posts very practical and high-quality content on improving your range of motion.

There is certainly some overlap between each phase of the MSS process, but of course the fun part is the 3rd phase: strength. This is your tried and true powerlifting training. 5×5, 3×3, 6×8… whatever your program calls for to get you stronger is what works here. By using the range of motion you have available to you, regular strength training through those ranges of motion will help you to hold on to your newly acquired mobility and stability.

Using The MSS Process In A Squat

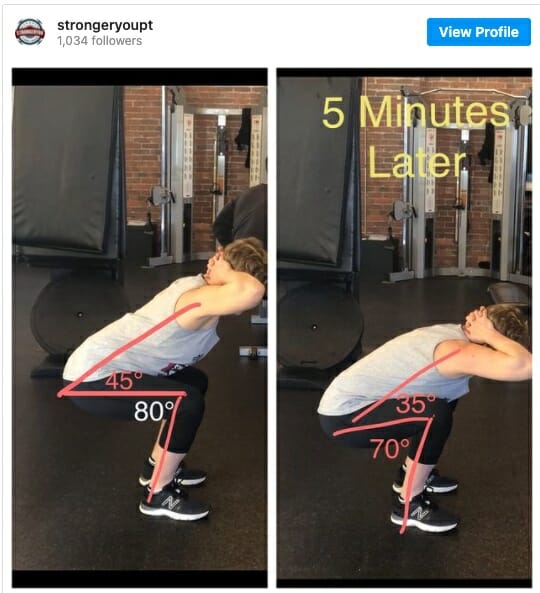

Using the squat as an example, , if you don’t have enough hip flexion to get to a powerlifting depth, it’s common to see the lower back tuck into flexion at the bottom of the squat to artificially create more range of motion in the squat. While your hip crease does go lower, the stress of the movement shifts from the hip joint (excellent at tolerating high forces through varying positions) to the lumbar spine disks and vertebrae (excellent at tolerating forces from a static, “neutral” position, relatively weak against shear and compressive forces when put into dynamic flexion).

While it’s not a guaranteed back injury if your lumbar spine rounds on a squat, many studies have shown the best way to herniate a disk is repeated flexion/extension of the spine. Adding weight to the equation just accelerates that process by increasing the applied load on the spine. If you were working on not injuring your spine so you can lift more in the long term (see my last article showing how you can get WAY stronger this way here) or coming back from a back injury, a simple approach would be twofold:

Squat to the maximum depth that your hip mobility will allow for,

Have a plan in place for improving your hip Use that new hip mobility in each session to gradually build your squat depth. While you won’t be squatting to “depth” at first, your risk of injury will drop significantly, and as your mobility improves, you will get to a full range of motion squat. The other side of the coin is you don’t worry about addressing your range of motion problems, potentially get injured, and then can’t train anyways…. Which will make you weak. Long term gains outweigh short term every single time.

- Add Variation to Your Training

Now that we’ve covered the cornerstones of proper movement, let’s take a look into some programming considerations.

When you train for any sport, your goal is to drive adaptations specific to the tasks. This can result in imbalances in both movement and muscular strength. With powerlifting being a completely bilateral (both sides work at the same time in the same way) sport, activities that take place on one leg (walking and running), and one arm (rotating the shoulders in gait, throwing) tend to become compromised as the body adapts to being strong on both sides at once.

As such, the best way to counter this adaptation is to include some training through planes of motion that aren’t trained with the powerlifts by themselves – effectively front loading your rehab work which you would have to do if you got injured anyways. Including one or two days of single leg work, frontal plane core work (side planks) and thoracic rotation (crawls, 1 arm pressing, etc) are some easy ways to implement this idea into your training without including so much extra volume that it detracts from your regular training. For more ways to program your accessory work, take a look at the most popular article on this site: How To Program Your Powerlifting Accessory Work, or for a more detailed approach, consider purchasing The Definitive Powerlifting Accessory Manual from the StrongerYou EBook Store.

- Take a Long Term Outlook

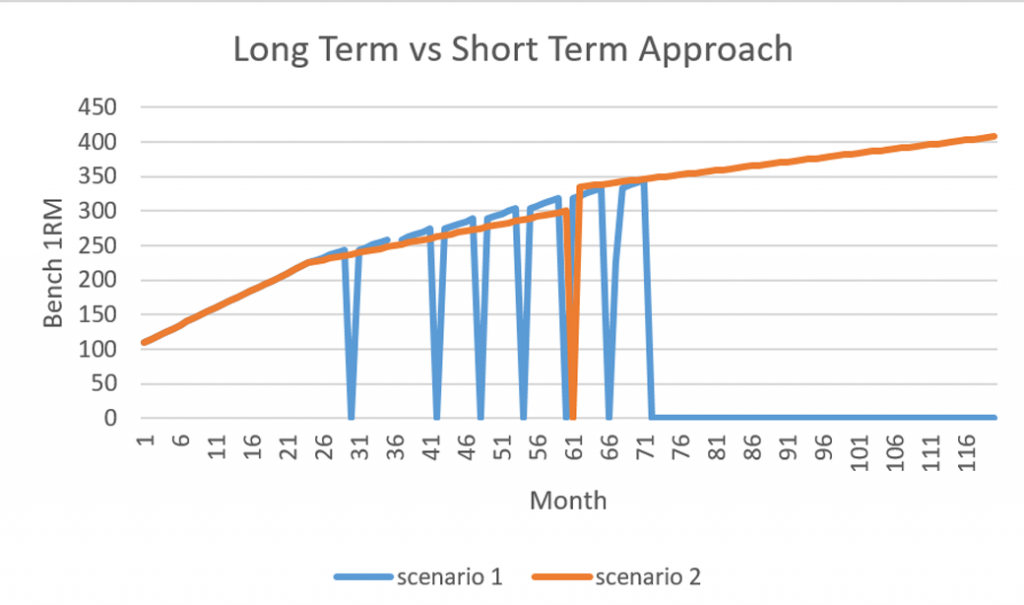

The last point I want to make here is that powerlifting is not a race. If you think you’re going to be at the top of the sport in 3 years, odds are you’re sorely mistaken. I won’t say it’s impossible because I’ve seen some truly gifted athletes make incredible progress, but you’re probably not one of them. Good sustainable progress will always outperform short-term, overly aggressive training programs. Even if you don’t get injured, you can’t really run Smolov or other super high volume, high intensity programs forever – training just doesn’t work that way.

If you are pushing volume or intensity so hard that your form breaks down, you should probably be mindful of what percentages of your 1RM you are using (strength gains are generally best seen at 75-90% of 1RM with moderate volumes. This works out to sets 3-6 reps, roughly speaking). Not only are you exposing yourself to increased injury risk with consistent form breakdown, but you’re probably just burning yourself out for little to no gain in the long term. While harder (closer to failure) sets can produce a stronger adaptation response, they are generally at the cost of increased overall stress on the system. Part of good programming is finding the balance between pushing hard enough to drive progress but not so hard that you burn yourself out or get injured.

If you want to see how “taking it easy” can yield vastly larger results when compared to a “hardcore” training approach, take a look at my I Haven’t Gotten Injured [Yet] article.

Wrapping Up

As much risk as there is with powerlifting training, when done right, you can substantially reduce these risks and even increase your results by having a plan, respecting your own mobility restrictions, including appropriate amounts of variation, and keeping a long term outlook with your programming.

PS – Here’s 3 ways I can help you get stronger:

3. Apply to join my “Momentum Program” and become a case study. We’ll work with you 1-on-1 (in-person or online, depending on location) to consistently increase your PRs.

It takes less than 60 seconds to apply HERE in order to find out more information and see if you’d be a good fit.